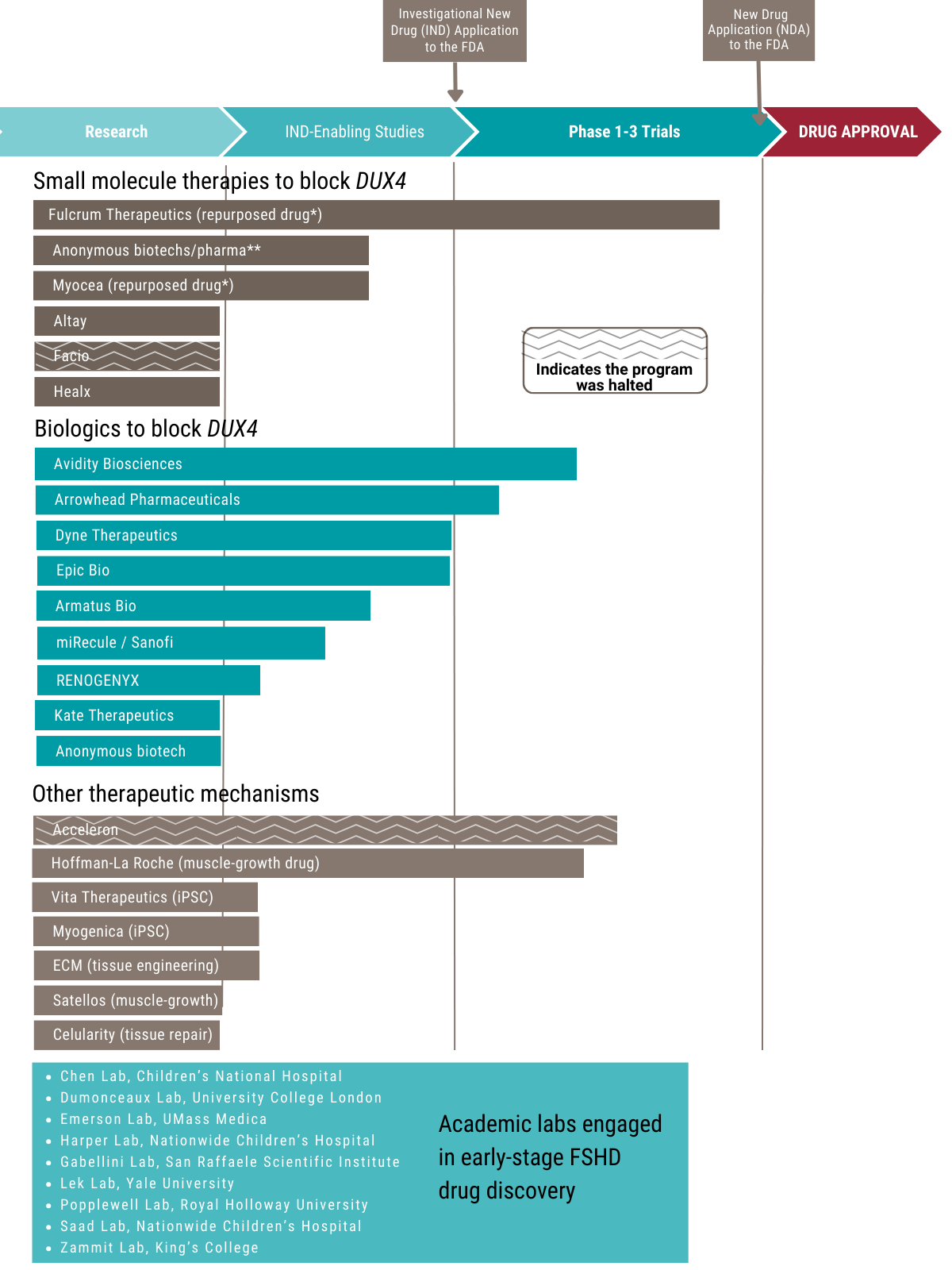

Growing numbers of companies and academic laboratories are pressing forward with early-stage drug development efforts.

This chart shows how far various candidate anti-DUX4 drugs have progressed along the path to FDA approval. DUX4 is considered a key gene causing FSHD Types 1 and 2.

*Repurposed drugs - compounds that were developed for other diseases and tested in the clinic. Some of them may have been approved for treatment of a specific disease, while others may have been shown to be safe but failed to be effective in these other indications and thus were abandoned. When a repurposed drug is found to work in the Target ID stage, it can often rapidly advance to the clinic, saving years and millions of dollars in preclinical testing.

**Anonymous biotechs & pharmas - many companies operate in stealth mode for business reasons. The FSHD Society maintains relationships with these companies, providing assistance to get their FSHD programs off the ground. When they go public, we will update you, so stay informed by signing up for email alerts and following us on social media.

The drug development process begins with finding a “target,” or biological disease mechanism, that can be modified by a therapy. Candidate compounds are identified based on their ability to “engage the target” and alter the disease mechanism (typically done in a test tube). Compounds that have the best properties to succeed as a drug are selected to be a “lead” (this is “lead optimization”). Lead compounds then go through a series of “preclinical” experiments, such as testing in an animal model. If a compound looks promising, a company may file an investigational new drug (IND) application with the FDA seeking permission to begin clinical trials in humans. The drug must then go through several trial phases before the company can file a new drug application (NDA), seeking permission from the FDA to put the drug on the market.

Small molecule drugs are chemical compounds that consist of up to about 100 atoms and are made through chemical synthesis. Being small, they can be more easily administered, for example, as a pill and pass through the digestive tract into the bloodstream to reach and penetrate cells. Biologics are very large molecules (such as RNA and proteins) derived from living organisms. They tend to be more precise and targeted, and therefore more effective. Because of their large size, they are usually delivered by injection or infusion, and getting them inside cells can be challenging.

Note, there are other proposed interventions, including nutritional supplements, nonpharmacologic interventions, growth hormone, etc., but they are not currently included in this diagram. Our colleagues at the FSHD UK patient registry maintain a broader list of therapies in development, including those in very early stages.