by Allison Calder, Salt Lake City, Utah

Did you know the first grant ever paid out by the United States National Institutes of Health (NIH) was awarded to study FSHD? Maybe you are as shocked as I was when I first heard this while sitting in a family conference at the University of Utah a couple of years ago. I felt excited to know that FSHD research had such a monumental beginning. But it also led me to wonder about the impact of this research, begun in the 1940s, and how it has progressed since then.

Did you know the first grant ever paid out by the United States National Institutes of Health (NIH) was awarded to study FSHD? Maybe you are as shocked as I was when I first heard this while sitting in a family conference at the University of Utah a couple of years ago. I felt excited to know that FSHD research had such a monumental beginning. But it also led me to wonder about the impact of this research, begun in the 1940s, and how it has progressed since then.

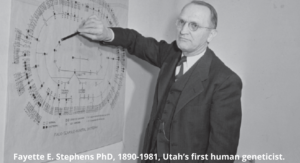

Passed in 1944, the Public Health Service Act gave the NIH the new ability to give grants to researchers. In 1945, the NIH awarded its first grant to Maxwell M. Wintrobe, Frank H. Tyler, and Fayette Stephens from the University of Utah. Tyler was a founding father of the University School of Medicine and a distinguished physician-scientist, and Stephens, a founder of the American Society of Human Genetics. With this grant, the researchers pursued an investigation into the clinical manifestations and inheritance of FSHD in a large Utah kindred.

The progressive muscular dystrophy observed in this family was followed closely by Samuel C. Baldwin (1855-1944), a prominent Salt Lake City orthopedist. Baldwin introduced this family to Stephens in the mid-1930s and they began a formal study of the inheritance of FSHD. This research, published in 1950, presented a detailed description of FSHD in members of a family consisting of six generations descended from one individual who was affected by FSHD who emigrated from England with other pioneer families in the 1850’s. Of the 1,249 descendants included in the data, 240 were reviewed clinically and also provided blood samples, which were studied as well as possible for the era.

This publication was remarkable for many reasons:

- Since the original reports of “Myopathie Atrophique Progessive” by Landouzy and Dejerine in 1886, this was the largest pedigree described.

- A clear clinical classification of FSHD was given for the first time.

- The autosomal dominant inheritance pattern of FSHD was described.

- Variability in severity of expression was observed: “…the severity of the disorder in the parent had little influence on the severity of the condition in the children.”(Stephens & Tyler)

What happened next?

That first grant was renewed annually for 33 years. The research was continued in the 1980s by Mark Leppert, one of the pioneers of human gene mapping. He collected clinical data from members of the original kindred and their descendants and also collected DNA samples for future analysis. At the same time, Daniel Perez and Stephen Jacobsen, founders of the FSHD Society, were also collecting samples from the same kindred. After a 1990 report in Dutch families mapping the FSHD locus to chromosome 4q, Leppert and Kevin Flanigan at the University of Utah used these DNA samples to demonstrate that the length D4Z4 contraction was passed stably across many generations in a 2001 research article (see references). More recently, the Peter Jones laboratory at the University of Reno published a report characterizing the original cell lines collected by Perez and Jabobsen and these cell lines are now available from the Coriell Institute to researchers throughout the world.

Why does this matter today?

In the conclusion of that first research article, Tyler wisely observed, “It would seem that a dominant gene for dystrophy is transmitted but that the severity of its expression depends upon the environment and the remaining genotype of the individual concerned.”

This hypothesis is being studied today at the University of Utah by Russell Butterfield and Robert Weiss as part of a collaboration with Charles Emerson and the University of Massachusetts Wellstone Muscular Dystrophy Cooperative Research Center for FSHD. There are now nine generations, identified over 70 years, of investigation included in the data. Even more astonishing, however, is that of the historical samples from those 200-plus collected in the 1980s and 90s, many are still of good enough quality that they can be used in modern genetic analysis tools today. In other words, the researchers have access to genetic and clinical information for the family tracing back to the 19th century.

In the study of this large family group is the opportunity to discover which genes could control the disease and its severity. By gaining this understanding, clinicians may be able to better predict the severity of FSHD expression in individuals (wouldn’t it be nice to know what to expect?). It may also be possible to create targeted treatments based on those genes that affect severity. The discoveries are exciting, and the possibilities are endless.

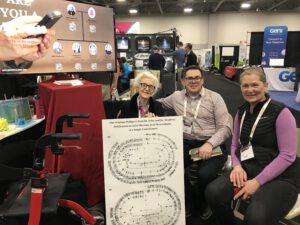

While the majority of this family remained in Utah and the intermountain West, several of these family lines may have relocated across the US and possibly even internationally. In an effort to reach additional members, the research team in Utah recently participated in RootsTech, the largest genealogy conference in the world. There they talked to participants about muscular dystrophy and the historical significance of this kindred. At the conference, the team was able to identify several individuals with connections to the original family. As a highlight, the team met Beverly Dalley, now 96 years old. Not only is Beverly a part of the original kindred (VI-140, part of an unaffected branch), but she is also the artist who hand-drew the original pedigree with 1249 individuals!

If you would like to learn how you can participate, point your smartphone camera at the QR codes in this article or contact Sarah Moldt, research coordinator at the University of Utah, at sarah.moldt@hsc.utah.edu or 801-585-9399.

References

References

Studies in disorders of muscle. V. The inheritance of childhood progressive muscular dystrophy in 33 kindreds. Stephens FE and Tyler FH. Am J Hum Genet. 1951 Jun;3(2):111–125.

Location of facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy gene on chromosome 4. C. Wijmenga, R.R. Frants, O.F. Brouwer, P. Moerer, J.L. Weber, G.W. Padberg. Lancet, 336 (1990) pp. 651-653.

Genetic characterization of a large, historically significant Utah kindred with facioscapulohumeral dystrophy. Flanigan KM, Coffeen CM, Sexton L, Stauffer D, Brunner S, Leppert MF. Neuromuscul Disord. 2001 Sep;11(6-7):525-9.

Large family cohorts of lymphoblastoid cells provide a new cellular model for investigating facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Takako I. Jones, Charis L. Himeda, Daniel P. Perez, and Peter L. Jones. Neuromuscular Disorders, 23 (2016) pp. 975-980.

Leave a Reply